The Way We Were

By Rachel Lim

Four watercolour masters capture the shifting landscapes and lifeways of twentieth-century Singapore.

“Oils are like the novels of visual art, while watercolours are the poems.”

This quote, by the Singaporean watercolourist Ong Kim Seng, opens the second chapter of the exhibition catalogue Passion for Landscapes. And indeed it aptly describes the appeal of the watercolour medium. Rather than aspire to the grandeur of oil painting, watercolour rests content in its own smallness, even insignificance. Like a poem, a watercolour painting can capture and freeze a single moment in time—and it is perhaps precisely this quality that makes it linger in the mind long after.

Watercolour arrived in Singapore through European colonial influence, but was soon adopted by local artists. Gradually, a repertoire of favourite subjects emerged, including kampongs (villages), old streets and shophouses, market stalls, and the ever-popular Singapore River. As Singapore urbanised at astonishing rates, the artists witnessed the island transform in front of their eyes. They continued to paint the usual subjects, but construction sites, high-rises, and other markers of modernity also appeared in their paintings.

Generally, the watercolourist is perhaps less interested in documenting an important historical moment than in capturing the colours of the sea or the quality of light on a particular day. But, consciously or inadvertently, Singaporean watercolourists became chroniclers of these strange times and of Singapore’s changing landscapes and lifeways. This essay spotlights four of these artists—Lim Cheng Hoe, Gog Sing Hooi, Leng Joon Wong, and Ong Kim Seng—and the techniques and themes which connect their lives and careers.

Lives of the artists

These four artists came from varied backgrounds and embarked upon different career trajectories. Lim Cheng Hoe (b. 1912), the oldest of the four, was born in China but moved to Singapore at a young age. During his studies at Raffles Institution (RI), he studied art under Richard Walker, an influential British administrator and educator. Though he had to balance his artistic pursuits with his career as a clerk, Lim eventually became one of Singapore’s most prominent and beloved watercolourists.

Photo: Lim Cheng Hoe

Born in China in 1933 and 1947 respectively, Gog Sing Hooi and Leng Joon Wong both graduated from Singapore’s Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) in the 1960s. Gog, who had previously lived in Malaysia, moved to Singapore in 1957, where he juggled artistic studies, teaching duties, and courses at the Teacher’s Training College. Leng, meanwhile, only became a full-time artist after spending thirteen years as a graphic designer.

Ong Kim Seng (b. 1945) is the only one of these artists born in Singapore. Like Lim, he did not benefit from formal art academy training. Ong worked various jobs, including advertising apprentice, welder, policeman, and A/V technician, before finally becoming a full-time artist in 1985. Dubbed a “Wordsworth of Watercolour,” Ong garnered acclaim abroad as the first non-American Asian member of the American Watercolour Society (AWS), the first Singaporean to win seven AWS awards, and the recipient of its prestigious Dolphin Fellowship. He also received Singapore’s Cultural Medallion in 1990.

Of these four artists, one was born in Singapore, two moved to Singapore as children, and one arrived in Singapore as an adult. Two attended art academies, while the other two can be considered primarily self-taught. Ong and Leng managed to carve out full-time art practices, but Gog and Lim practised alongside careers in teaching and the civil service.

Despite these differences, as one reads the literature and archives surrounding these artists, a few unifying themes emerge. The artists shared a dedication to plein-air (outdoor) painting and the watercolour medium, bonds of camaraderie and mentorship, and an interest in capturing the shifting landscapes and lifeways of Singapore.

Attaining artistic mastery

The practice of plain-air painting emerged in Europe during the 1800s. Rather than sketch outdoors and return to the studio to complete their works, as was traditional, artists like the French Impressionists began to paint whole works outdoors. The practice eventually made its way into art academies and curricula not only in Europe, but also other parts of the world—Singapore included.

The practice of plain-air painting emerged in Europe during the 1800s. Rather than sketch outdoors and return to the studio to complete their works, as was traditional, artists like the French Impressionists began to paint whole works outdoors. The practice eventually made its way into art academies and curricula not only in Europe, but also other parts of the world—Singapore included.

Chia Wai Hon writes, “[M]ost Singapore watercolourists, if not all, are impressionists, plain-air artists who carry their easels outdoors and paint on the spot to capture effects of light and atmosphere, and to reproduce physical features as observed.” Dedicated to this practice, artists would travel throughout Singapore looking for picturesque scenes, often revisiting favourite sites multiple times.

Through close observation and finely honed skills, they transformed these scenes into convincing and appealing artworks. With its translucency, blendability, and ability to both cover broad areas and render delicate details, watercolour was the perfect medium to capture the ephemeral effects of light and weather. Furthermore, its easily portable and quick-drying nature made it practical for plein-air painting.

For many painters, the choice of watercolour was also guided by economic concerns, as watercolours were more affordable than oils. Economic constraints shaped their lives in other ways, making it difficult or impossible to attend academies or pursue art full-time. Focused on nation-building and modernisation, mid- to late-twentieth century Singapore was not the most conducive environment to carve out an art career.

Yet, Lim, Gog, Leng, and Ong all approached their art with dedication and verve, filling weekends and spare time with painting practice. Reading art publications, meeting with other artists, and visiting exhibitions also helped them learn and improve. Though neither received academy training, Lim continued to attend Richard Walker’s informal Sunday classes even after graduating from RI, while Ong took classes under the Equator Art Society, a social realist art group.

Ultimately, describing these artists as “amateur” or “self-taught” is less a critique of their skill than a recognition of their commitment and drive.

The ties that bind

Artist groups were also instrumental in developing the talents of Singaporean watercolourists. During the 1950s-1960s, several Singaporean artists were part of the Sunday Painters, so named because they met regularly for Sunday painting sessions. Toting their art supplies across the island, they often worked from morning to afternoon, visiting multiple locations in a single day. These friendly and casual meetings provided invaluable opportunities to watch fellow artists at work, learn from more seasoned practitioners, and receive useful critique.

In 1969, this network was formalised with the inauguration of the Singapore Watercolour Society (SWS). Lim, Gog, and Leng were among its founder-members, while Ong joined at a later date.

Over time, the Singapore watercolour community cultivated lasting, productive friendships. These relationships must have been a great source of encouragement and inspiration—perhaps particularly for those who did not have academy experience. Low Sze Wee writes: “…Lim’s Sunday painting sessions with fellow artists probably provided him with one of the most sustained and substantial modes for informal learning through social interaction.”

Lim, in turn, was seen as a mentor by many, including Gog, Leng, and Ong, who then went on to transmit their skills and knowledge to still younger artists.

Lim even embarked on multiple painting expeditions to Malaysia with artists including Gog. In 1996, then-SWS president Ong was instrumental in realising a posthumous President’s Charity Art Exhibition for Gog. Incidents like these illustrate the respect and camaraderie between the Singaporean watercolourists.

Scenes of Singapore

The Singaporean watercolourists produced work on a variety of subjects, basing their paintings on real Singaporean vistas but overlaying them with subjective impressions and moods. A simple street scene, for instance, could be suffused with a sense of tranquility, melancholy, or nostalgia.

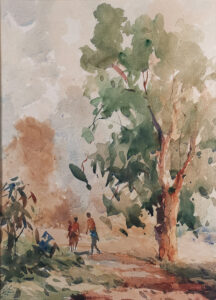

Favourite topics included nature, seaside, river, and kampong scenes. Lim, for one, was a great nature enthusiast and “inveterate walker,” as described by art historian T.K. Sabapathy. From his forays into nature he produced many paintings of trees, such as Nature Trail. Small figures populate these landscapes, but the emphasis is on the graceful tree forms and the sunlight falling through branches and leaves. In his beach scenes, meanwhile, colour washes melting softly into each other convey the shifting appearances of sea and sky. As curator Constance Sheares writes: “…he constructed a friendly and vivacious world with which we can easily identify.”

Besides nature, the watercolourists also enjoyed kampong scenes. As public housing replaced Singapore’s traditional villages, these paintings became nostalgic records of a vanishing way of life.

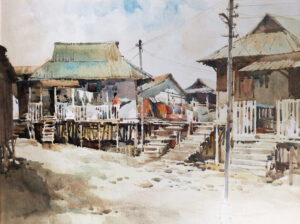

Gog Sing Hooi’s Kampong at Jalan Fatimah Woodlands

One such work is Gog’s 1986 Kampong at Jalan Fatimah (Woodlands). Known for his mastery of transparent watercolour painting, in which the pigments are not mixed with opaque white paint but instead rely on the white ground of the paper for brightness, Gog often painted the same scene from the same vantage point multiple times. This sometimes cramped his originality, but also allowed him to perform feats such as painting completely from memory.

Kampong at Jalan Fatimah, for instance, can be compared to Woodland Kampong of the same year, published in the catalogue for the 1996 President’s Charity Art Exhibition. In both paintings, the seeming timelessness of the serene village scene is disrupted by the addition of telephone poles, reflecting, perhaps, the gradual creep of modernity to all corners of the island.

Ong Kim Seng’s Singapore River

Similarly, Ong Kim Seng’s Singapore River—an iconic subject which the watercolourists painted over and over again—juxtaposes old and new. The vertical orientation of the painting emphasises the modern high-rise which looms over the river’s traditional boats and shophouses. As one of Singapore’s most respected watercolourists, Ong is recognised for his careful contrast of light and dark elements and his use of colour to create mood. Here, the soft shadows on the buildings, the warm and harmonious colour palette, and the wispy branches reaching delicately across the frame all reflect his painterly skill.

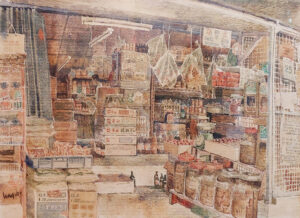

Finally, though the watercolourists were primarily landscape painters, they were also interested in Singapore’s small businesses and trades. Paintings that reflect this interest include Gog’s Roasting Coffee (1987) and Leng Joon Wong’s Ice-ball Man (1978). In Wee Nam Road (1997), Leng creates an extraordinarily detailed rendering of a convenience store, capturing everything from the date on the tear-away calendar to the brands of foodstuff for sale.

Leng Joon Wong’s Wee Nam Road

Intent on his newspaper, the shopkeeper seems unaware of our presence, giving the image the immediacy of a candid photograph though it must have taken hours to complete. Through this immersive watercolour, Leng invites us into the warm and colourful environment of the old store.

The watercolour medium is sometimes treated dismissively as the domain of hobbyists and amateurs. Yet, as the study of these artists attests, watercolour is an important chapter in the story of Singaporean art. Devoted to art even amidst challenging circumstances, Lim Cheng Hoe, Gog Sing Hooi, Leng Joon Wong, and Ong Kim Seng forged fruitful relationships with other watercolourists and laid a foundation for the future development of Singaporean watercolour art. Their bodies of work are not only valuable reminders of life in old Singapore, but also testaments to their dedication to their art.

Selected bibliography

Gog, Sing Hooi. Gog Sing Hooi, 1933-1994: A Dedicated Singapore Watercolourist. Singapore: President’s Office; Singapore Watercolour Society, 1996. Exhibition catalogue.

Koh, Buck Song. Heartlands: Home and Nation in the Art of Ong Kim Seng. Singapore: Ong Kim Seng, 2008. Exhibition catalogue.

Lim, Cheng Hoe. A Collection of Water-Colour Paintings. Singapore: Education Publications Bureau, 1980. Exhibition catalogue.

Lim, Cheng Hoe. Lim Cheng Hoe Retrospective, 1986. Singapore: Ministry of Community Development, 1986. Exhibition catalogue.

Low, Sze Wee, ed. Lim Cheng Hoe: Painting Singapore. Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2018. Exhibition catalogue.

Ma, Peiyi. Passion for Landscapes: The Watercolour Art of Ong Kim Seng. Singapore: artcommune gallery, 2013. Exhibition catalogue.

Ong, Kim Seng. Nostalgia in Transformation. Singapore: Ode to Art, 2014. Exhibition catalogue.

Ong, Kim Seng. Poems in Watercolor. Singapore: Galerie Belvedere, 2010. Exhibition catalogue.

“Plein air.” Tate. Accessed January 14, 2023. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/plein-air.

Poh, Lindy. Living Colours: Works of Art from the Times Collection. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2005. Exhibition catalogue.

Sullivan, Michael. Art and Artists of Twentieth-Century China. Berkeley: University of Chicago Press, 1996. https://books.google.com.sg/books?id=ku7dKvDDOuIC.

Tan, Chee Khuan. Penang Artists: 1920’s – 1990’s. 2nd ed. Penang: The Art Gallery, 1992.